The Byzantine Empire: The Continuation of Rome in the East

The Roman Empire did not end in the 5th Century AD. In Fact, it lived on for a thousand years more as what modern historians called: The Byzantine Empire. It emerged around the 4th century in the eastern part of the Roman Empire as it gradually divided into two. It is characterized by its longevity, tracing its origins to the very foundation of Rome, although the dating of its beginnings varies according to the criteria chosen by each historian. The year 330, marked by the founding of Constantinople as its capital by Constantine I, or 395, with the definitive division of the Roman Empire, are the two most commonly adopted dates of birth. More dynamic than the Western Roman world, whose effective administration increasingly became the work of barbarian elites following their gradual arrival by treaty or conquest, the Eastern Empire gradually asserted itself as an original political construction. Undoubtedly Roman, this empire was also Christian and primarily Greek in language. In 476, when the last Western emperor abdicated, the Byzantine emperor became the sole sovereign of the Roman Empire in title.

Situated on the border between East and West, the Byzantine Empire mixed elements from Antiquity with innovative aspects of a Middle Ages sometimes described as Greek. It became the seat of an original culture that extended well beyond its borders, which were constantly assailed by new peoples. Part of Roman universalism, it managed to expand under Justinian I (emperor from 527 to 565), recovering part of the ancient imperial borders before experiencing a significant retraction. From the 7th century onwards, profound upheavals hit the Byzantine Empire. Forced to adapt to a new world in which its universal authority was contested, it renovated its structures and managed, at the end of the iconoclastic crisis, to experience a new wave of expansion that reached its peak under Basil II (who reigned from 976 to 1025). Civil wars and the appearance of new threats forced the Empire to transform again under the leadership of the Comneni, before being dislocated by the Fourth Crusade when the Crusaders captured Constantinople in 1204. Although it was reborn in 1261, it was in a weakened form that could not resist the Ottoman invaders nor the economic competition from the Italian republics (Genoa and Venice). The fall of Constantinople in 1453 marks its end.

Throughout its thousand-year history, both continuity and ruptures punctuated the existence of the Byzantine Empire, a complex entity to analyze in its diversity. Heir to a rich Greco-Roman culture, it preserved and transmitted this heritage to the West during the Renaissance. The empire developed its own civilization, deeply imbued with religiosity. As a pillar of the Christian world, it defended an Orthodox Christianity that influenced central and eastern Europe, where its legacy remains vibrant today. The separation of the Eastern and Western Churches marked a progressive rupture with Roman Catholicism.

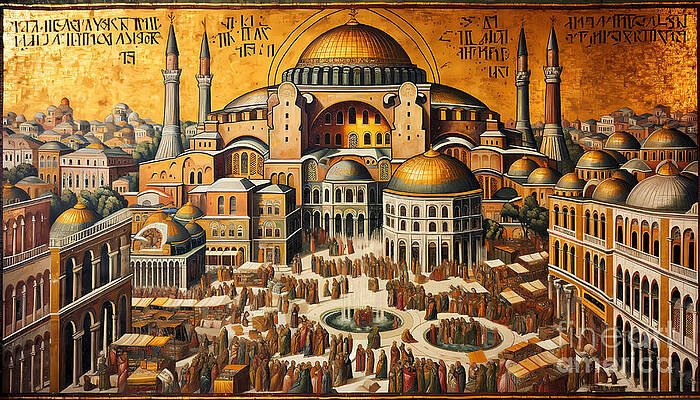

Described as “archaic” or “declining” in ancient historiography, sometimes imbued with mishellenism, the Byzantine Empire demonstrated a remarkable capacity for adaptation in response to global developments and constant threats, often on multiple fronts. It skillfully employed both diplomacy and force to contain its enemies. Its exceptional location, at the crossroads between East and West, blurred the borders between the Mediterranean world and the Pontic basin, allowing it to develop a dynamic economy, symbolized by its currency, which was often used far beyond its borders. This same wealth also attracted ambitious neighbors who regularly challenged the powerful walls of Constantinople. This city, even more than Rome for the earlier Roman Empire, was the center of the Byzantine world. Even during its decline after 1204, it maintained a cultural vibrancy that contributed to the emergence of the European Renaissance.

Judgments on the Byzantine Empire have varied profoundly over time. Considered a model to follow by the absolutist regimes of the 17th century, it was strongly denounced in the 18th century by critics of absolutism as decadent. These interpretations have given way to more scientific historical perspectives. The heritage of the Byzantine world is crucial for understanding the Slavic world, to which it bequeathed an alphabet and a religion. Beyond that, it shone by transmitting codified Roman law, architectural masterpieces embodied by Hagia Sophia, and, more broadly, an original culture.

1 comment

Wow what a site!! My three children have been given my list for Christmas. One thing …… in a number of images Hagia Sophia is portrayed with minarets. Please can I suggest the pics are edited and minarets removed Ta!